What Car Wasfatima Blush Driving in Never Say Never Again

Sean Connery co-wrote a Bond film that was never made

The original 007 co-wrote a caper about nuclear bomb-carrying sharks. It was called Warhead, and elements popped up in later films, writes Nicholas Barber.

J

James Bond has done some memorable things in his time, from dodging laser blasts on a space station to driving an invisible car across a glacier. One thing he hasn't done, however, is deactivate a robot shark which is carrying an atom bomb through a Manhattan sewer. But he very nearly did. In 1976, a Bond screenplay revolved around a shoal of remote-controlled, nuclear-weaponised robo-sharks. Its title was Warhead. And one of its three screenwriters was none other than the original big-screen 007, Sean Connery.

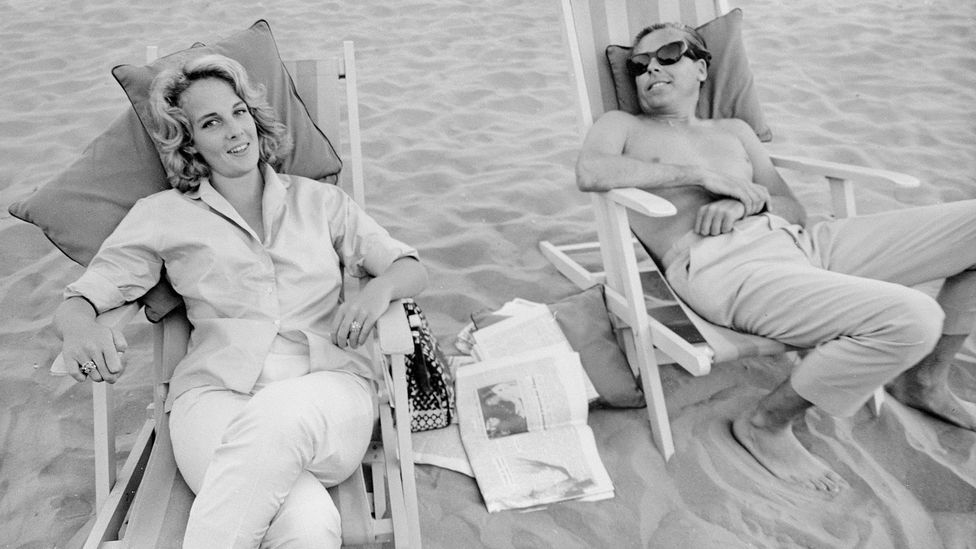

Another of the screenwriters was Kevin McClory, who had been introduced to Ian Fleming, the author of the Bond novels, back in 1958, well before any of them had been turned into films. He was almost as much of a Bond figure as Fleming himself. Fleming was a globe-trotting former British naval intelligence officer with a prodigious appetite for cigarettes and alcohol. McClory was a handsome Irish playboy who had served in the British Merchant Navy and had been engaged to Elizabeth Taylor. He had also written, produced and directed a film, The Boy and the Bridge, so when he asked Fleming if he could make the first ever Bond movie, the author felt that he was the ideal man for the job.

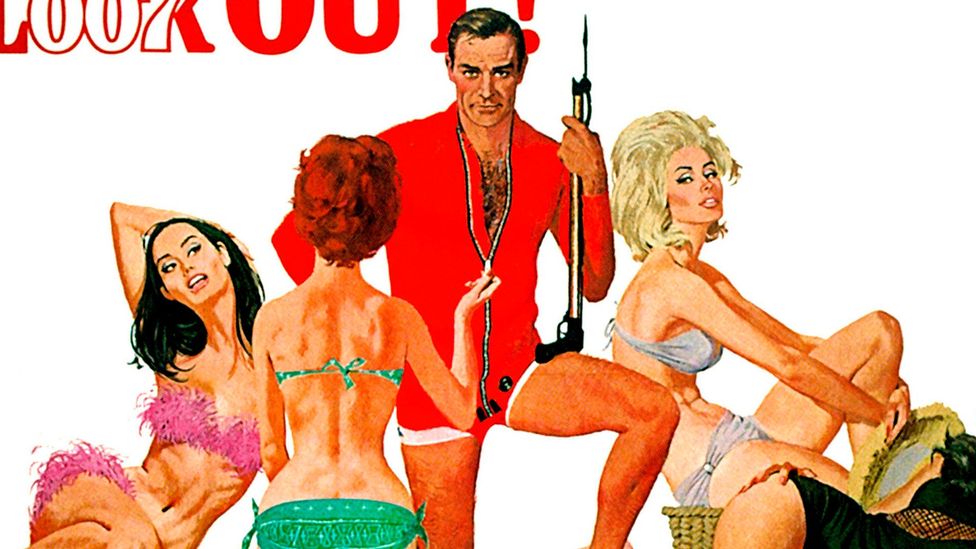

Thunderball was the fourth 007 film and, adjusted for inflation, it remains the most successful at the US box office – it would have outgrossed The Dark Knight (Credit: Alamy)

McClory's plan was that instead of adapting one of Fleming's published novels, they would concoct a new story with the help of an established screenwriter, Jack Whittingham. Several drafts were completed, some better than others: the results of one early brainstorming session had 007 going undercover as a cabaret entertainer, having been taught how to tread the boards by Noël Coward and Laurence Olivier. Mercifully, the revised plot concentrated on an international criminal consortium named Spectre, an organisation which hadn't featured in any previous Bond novels. One of its officers, Largo, was to steal two Nato nuclear missiles, but Bond would track him to the Bahamas before he could launch them. Fleming was happy with the premise, although not with the title, Longitude 78 West. He replaced it with a title of his own: Thunderball.

Kevin McClory, seen here at the Venice Film Festival in 1959, worked with Ian Fleming in the late 50s on a Bond screenplay that became the novel Thunderball (Credit: Getty Images)

For a while, it looked as if the film would be made, possibly with Alfred Hitchcock at the helm and Richard Burton playing the Secret Service's top agent and Martini aficionado. But Fleming began to suspect that McClory didn't have the experience to make an espionage blockbuster, after all. He decided instead to use the Thunderball screenplay as the basis of his next novel. Unfortunately, he didn't get around to consulting the two men who had done most of the work.

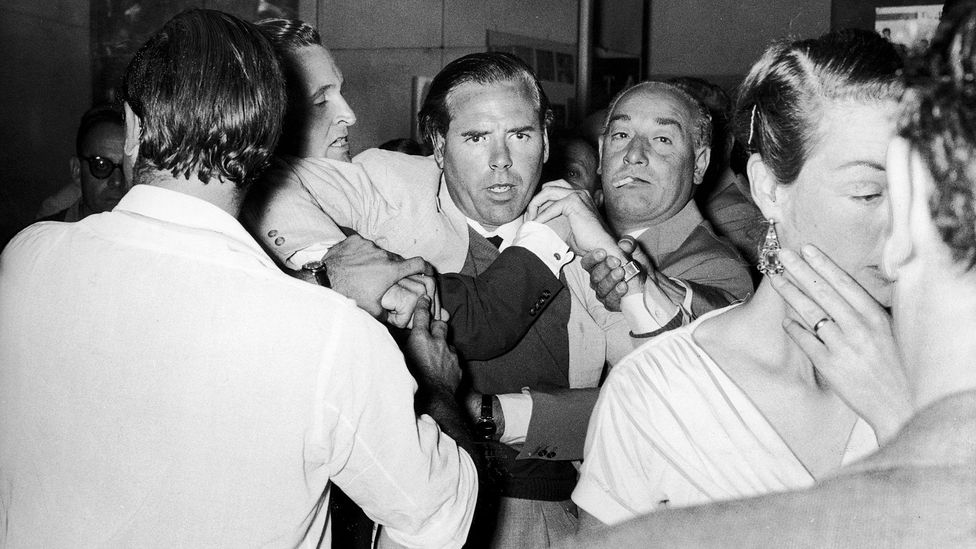

McClory, seen here in a bar room brawl in 1959, sued Fleming after the author chose other film producers to adapt Bond – but retained elements of his screenplay (Credit: Alamy)

McClory sued. Two court cases later, the judgement came down that subsequent editions of the Thunderball novel would acknowledge him and Whittingham, and that McClory would also retain film and television rights to the story. Meanwhile, two producers named Albert R 'Cubby' Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had launched their own series of Bond movies starring Connery. Their company, Eon, produced Dr No in 1962, followed by From Russia With Love and Goldfinger. Keen that Thunderball should be their fourth Bond film, they did a deal with McClory whereby he would be credited as producer, and he would have the right to remake Thunderball 10 years later: presumably they were banking on either the public or McClory losing interest in 007 before the decade was up.

It was only in McClory's 1950s Thunderball screenplay that criminal syndicate Spectre was introduced, along with supervillain Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Credit: Getty Images)

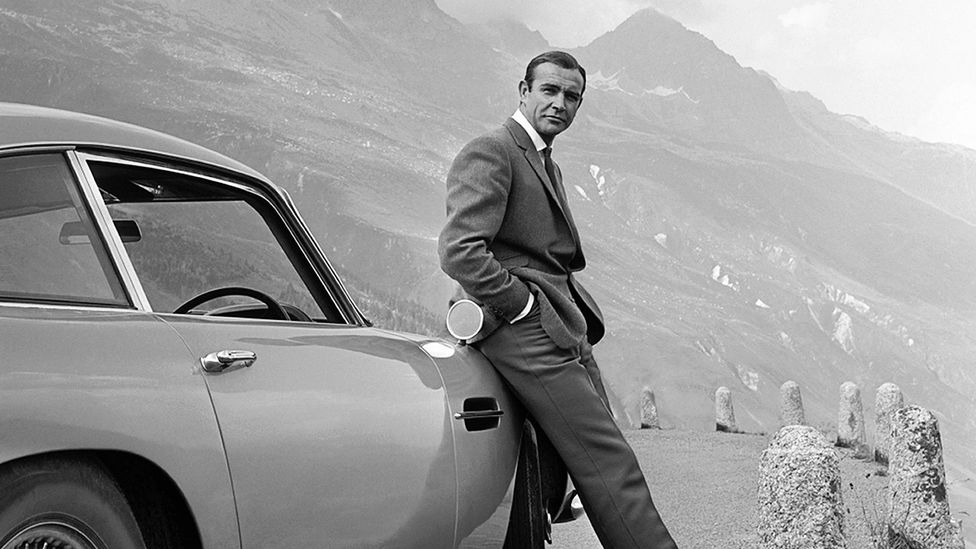

They were wrong on both counts. Thunderball was released in 1965, and when 1975 rolled around, McClory announced that his remake was going ahead without Broccoli and Saltzman. He even chose a title which would stake his claim to the character's cinematic incarnation: James Bond of the Secret Service.

Licence to chill

If that weren't provocative enough, he taunted his competitors at Eon by recruiting two co-writers who had once been friendly with them. The first of these was Len Deighton, three of whose novels had been made into Michael Caine films produced by Saltzman: The Ipcress File, Funeral in Berlin and Billion Dollar Brain. The second co-writer was Connery, who had hung up his Walther PPK and his waterproof toupee after 1971's Diamonds Are Forever. The actor had never written a screenplay before – or since, for that matter – but that wasn't the point. In Robert Sellers' definitive chronicle of the Fleming/McClory/Eon courtroom saga, The Battle for Bond, he argues that McClory's "real motive was getting Connery's name attached to his Bond project any which way he could".

However much or little Connery may have contributed, the screenplay was exciting enough to convince Paramount to back the film, now renamed Warhead. And it's certainly tantalising stuff. Even though the three screenwriters followed the rough outline of Thunderball, they sometimes went their own way, too, occasionally veering into the realms of Austin Powers-style parody. There is a Bond girl named Justine Lovesit. ("She does?" our hero inevitably enquires.) And there is a wonderfully farcical scene in which Bond has sex with Fatima Blush (actually a Spectre agent) while his cleaning lady, Effie (also a Spectre agent), is hiding under the bed. Immediately afterwards, two men break into 007's Belgravia flat, but he dispatches them with a karate chop and a kick to the groin, only to learn that they were on his side all along. The men, he is told back at MI6 headquarters, are "somewhat piqued".

McClory claimed the rights to Spectre and Blofeld, the primary nemeses of Connery's Bond except in Goldfinger – Eon Films could not use them for decades (Credit: Getty Images)

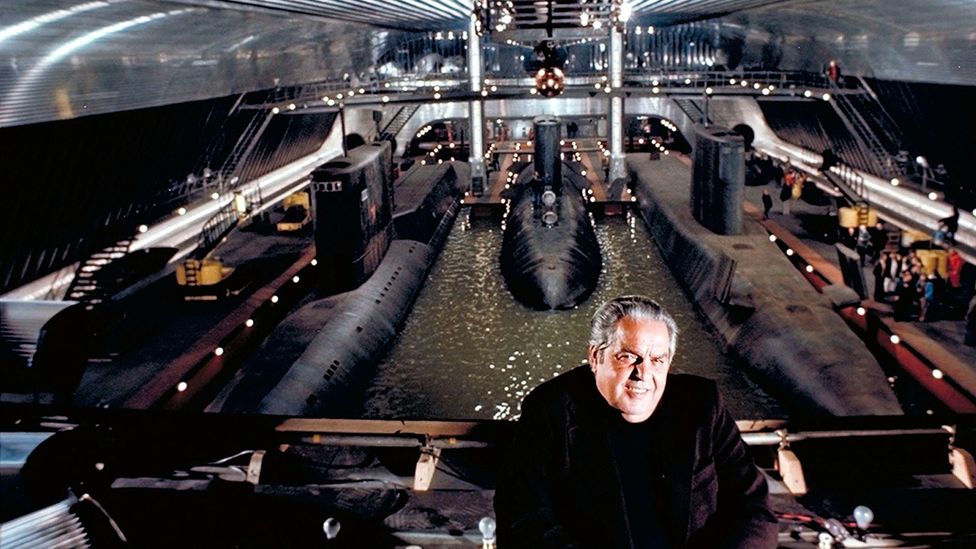

Another distinction between Thunderball and Warhead is the latter's crazily entertaining New York climax, which has Bond wrestling mechanical sharks in the sewers, then paragliding up to the head of the Statue of Liberty for a brutal fight with Spectre's goons. ("Blood trickles down the cheek of the Statue of Liberty like a tear," says the script.) And it's striking how much Warhead has in common with the Bond movie that Eon was developing at that very moment. In The Spy Who Loved Me, which stars Roger Moore, the villain's underwater lair bears a suspiciously close resemblance to the one described on the page by Deighton and company: "A gigantic white futuristic tubular structure rises out of the ocean." And Bond's final clinch aboard a luxurious escape pod can be found in the Warhead script, too. Take into account the sharks and the stolen nuclear weapons, and the similarities between Warhead and The Spy Who Loved Me would make anyone raise a Roger Moore-ish eyebrow.

McClory retained the remake rights to Thunderball, which featured scenes set underwater – Cubby Broccoli made his own aquatic-themed 007 film first (Credit: Alamy)

McClory's reaction was more extreme. He took out an injunction against Eon's film, but Eon had already taken out an injunction against his, so each side was now claiming that the opposition had pinched their material. Wary of being caught in the legal crossfire, Connery and Paramount withdrew from the project. The Spy Who Loved Me went ahead. Warhead didn't.

The underwater romp The Spy Who Loved Me injected new life into Broccoli's Bond series – McClory's Thunderball remake Never Say Never Again was a flop in 1983 (Credit: Alamy)

Not that McClory gave up. In 1983, he and another producer, Jack Schwartzman, completed a less ambitious, less robo-sharky Thunderball remake, Never Say Never Again, and in the 1990s he touted a third version, Warhead 2000. But by then the question which had always echoed around his efforts had grown too loud to ignore: who needed another Bond movie franchise when Eon's was already so successful?

Eon bought the rights from the late McClory's estate to depict Blofeld and Spectre for the first time since 1971's Diamonds Are Forever – Spectre came out in 2015 (Credit: Getty)

Still, it's hard to think about McClory without a quantum of sympathy, especially while you're watching The Spy Who Loved Me, the jokey high-tech marine extravaganza which is so comparable to the one that he, Deighton and Connery had envisaged. And it's hard to hear that film's theme song without wondering if his rivals at Eon were sending him a defiant, mocking message: "Nobody Does It Better".

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180703-sean-connery-co-wrote-a-bond-film-that-was-never-made

0 Response to "What Car Wasfatima Blush Driving in Never Say Never Again"

Post a Comment